These Four Colors Started Stephen C. Datz' Painting Career

By Chadd Scott on

Cadmium yellow medium, cadmium orange, alizarin crimson, and ultramarine blue deep.

When Stephen C. Datz began trying his hand as a plein air oil painter, those were the only four colors he used.

And titanium white.

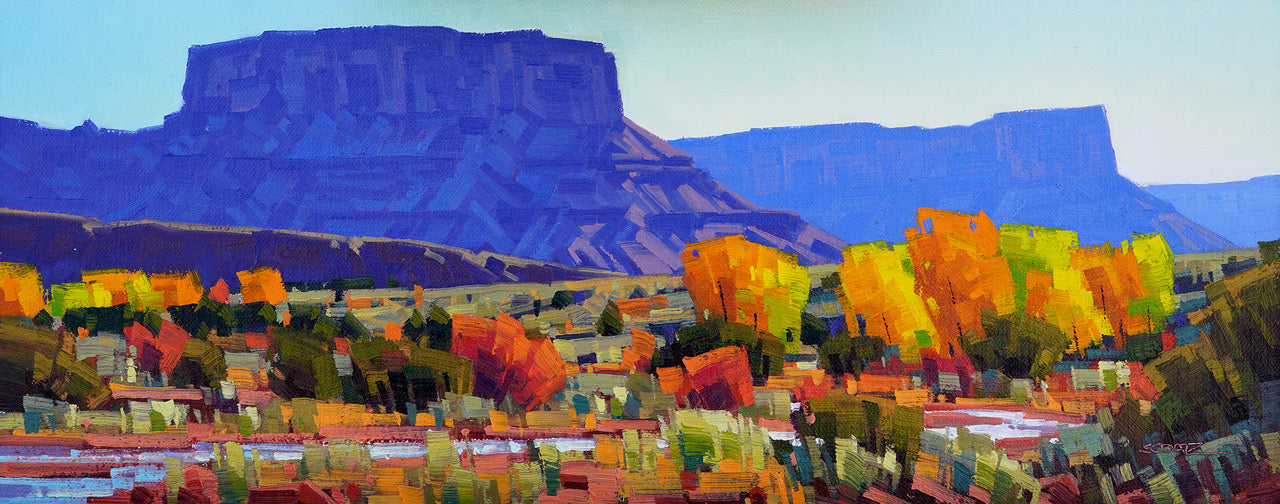

Stephen C. Datz - Ephemeral and Eternal, Oil on Canvas, 30" x 60"

More than a quarter century later into one of contemporary Western art’s most successful careers, he still remembers them.

“I did that on the advice of a fellow painter, who is a master; Ned Jacob suggested I paint with a limited palette because he said it's going to make you think about every color you mix,” Datz remembers. “The advice was, use (them) as long as you can, get as much out of (them) as you can, and at certain point, you're going to run into something that you want to paint and you can't make that color. That's when you start thinking about adding to your palette and expanding it.”

Over time, as his expertise has grown, Datz expanded his color palette. He’s up to about 11 now.

“As the palette expands you have more options, you can make more color, you can tweak colors with much more subtlety, especially when you start getting into grays and things that are not quite just like mixing blue and yellow,” Datz said. “When you're starting to see in desert rocks the very subtle colors, the more expanded palette can help you.”

Datz, who has been represented by Medicine Man Gallery since 2011, can see all the colors of the rainbow in desert rocks. Living and working out of Grand Junction, CO, Datz’ back yard is the Four Corners region. Countless painting trips across the area over the past two decades have trained his eye to notice the slightest details and the subtlest variations in color.

Along with incorporating more colors, Datz’ artistic evolution extends to his usage of them.

“I'm more persnickety about color. I take more time mixing and I take more time making sure that I have it right,” he said. “Sometimes with plein air, when you put yourself on that clock outside and you've got two, maybe two-and-a-half hours before you start risking over painting what you've got with what you're seeing two hours later, you sacrifice. It’s like, ‘I got the color mostly right, I'll just put it down;’ I've gotten a lot more focused on getting the color harmony exactly the way I want it, getting the right subtleties, the right coolness or warmness. It's a more deliberative process. My painting now, I probably spend more of my time by a factor of two to one mixing color than I do actually putting it down.”

The nature of working en plein air – outdoors – and Datz’ progression as an artist – and age – have resulted in other adjustments to how he works.

Stephen Datz in the American South West

“I've slowed down in terms of my actual painting. I'm not as fast as I used to be,” he said. “While the smaller (paintings) can be finished on location, I'm finding more and more that it's almost impossible. You typically have about a two-hour window on location and I can get most of the basic stuff down and done the way I want to in that window, but I find more and more that I'm just starting things outside, trying to get some basic information down, and then I bring them back to the studio and finish up there.”

Datz is describing intention.

The painstaking process of producing a painting. Thousands of individual decisions resulting in a finished artwork.

More than merely time.

I’ve found painters almost uniformly hate the typical “how long did that take you to paint” question. The real answer to “how long did that take you to paint” is “my entire life.”

To create that painting you’re seeing in the gallery, the artist used every lesson acquired over an entire life, and not just art school, life lessons. Every success, every failure, every triumph, every hardship, every lesson they’ve taken, every book they’re read, every painting that has worked and every one they’ve had to scrape down, start over, or throw into the trash throughout their entire life informed that painting.

That’s how long it took.

An utterly erroneous perception about art as being the result of spontaneous genius forms much of the public’s perception of how it is made. Artists lounging around, drinking, smoking, waiting for the thunderbolt of inspiration to strike them and then working in a frenzy to get that immaculately conceived idea out of their head and onto the canvas.

Nonsense.

Not even among the endless beauty of the desert Southwest.

Stephen C. Datz - Colorful Country, Oil, 6" x 15"

“Sometimes nature provides inspiration, but it's not perfect by any means,” Datz said. “You can see an idea, you can see a spark or potential, but at the same time, it's like, this would work better if this tree was moved over, or this would work better if I tweaked this color a little bit.”

Most artwork results from a grind. Trial and error.

Even the greatest painters – Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso – quit paintings, painted over, reworked canvases endlessly to achieve their desired results.

Despite what you may think, painting is hard work.

But as the old saying goes, “don’t tell me about the labor, just show me the baby.”

The baby hangs on the wall. Thousands of hours of labor – a lifetime – hidden in plain sight.

Look close.

Put your nose up to that painting.

Notice every brushstroke. Every color variation. Colors put on straight from the tube and colors mixed.

Think about all the individual decisions required to take that artwork from blank canvas to what appears before you.

Four colors can start a career, but it’s a lifetime which makes a painting.